What is Game Speed?

Let’s start by defining the term game speed. When we say game speed, we are referring to speed that you use within the context of sport competition. Basically, the type of speed that you actually use in a game.

In any sporting situation (or any human movement situation for that matter), there is always perception and action. We perceive (or see) something on the field, and we then take action (react) based upon what we see. We are always reacting to something.

The question then becomes, does speed training reflect the conditions that we see on the field? For most training programs, the answer is no…and that’s the problem. In a game there are numerous variables and conditions that effect how fast an athlete runs. Too often speed training is done in a way that isolates and dilutes those elements.

As physical preparation coaches, we believe it’s our job to best prepare our athletes for what they will see in a game. One way we accomplish this is by training game speed, and here are some of the way we do it.

Repetition without Repetition

Typical speed training protocols require athletes to execute speed drill after speed drill, searching for the perfect, ideal movement pattern. This way of coaching would is called “repetition with repetition”, or perfect practice. The problem with this is that sport is neither perfect nor ideal. Each situation is specific, every athlete is unique, and the conditions in sport are always changing.

Instead of adhering to a perfect practice model, we opt for a “repetition without repetition”, or imperfect practice model. The reality is, sports are always imperfect. An athlete cannot ask the ref to stop the play because he wasn’t ready and his feet weren’t in the right position. We are not searching perfection in practice, we are searching for learning and adaptability .

Modifying one or two variables within a speed session forces an athlete to learn, and adapt. The conditions in sport are not stagnant, so our training shouldn’t be either.

Application:

Simply changing the starting position of the athletes is a great way to achieve “rep without rep”. Changing the width of the athlete’s stance or which way the athlete is facing at the start of the drill is a great way to add variability.

Make Sprinting Open and Reactive

Let’s start by defining the terms open and closed drills/activities in our context. Open activities are ones the require decision making with conditions dynamic. Closed drills are ones where the is minimal decision making and the conditions are static. Think of reacting off a coaches whistle or “GO” and sprinting 10 yards.

Outside of a track and field, there aren’t many situations where athletes sprint just to sprint or reacting off a auditory command (closed). Even in that scenario, the 100 meter sprinter has other athletes in his visual field when he is competing, so there are other variables at play here.

Sprinting in sport is contextual and task-specific, which means an athlete is sprinting in reaction to something. Such as the movement of their opponent, or the sight/sound of a metal bat hitting a ball. Think of a linebacker in football running towards the ball carrier or an outfielder in softball running to make the catch. In both of those situations, the athlete must make quick decisions and anticipate where to be. In addition to that, there are consequences if they do not make they play.

Sprinting in those situations is much more physically and mentally cognitively demanding than running to a cone or reacting off a whistle. Knowing that, why would our speed training stop at closed (no decision making) speed drills?…Remember, our goal is to prepare the athletes for what they are going to experience on the field.

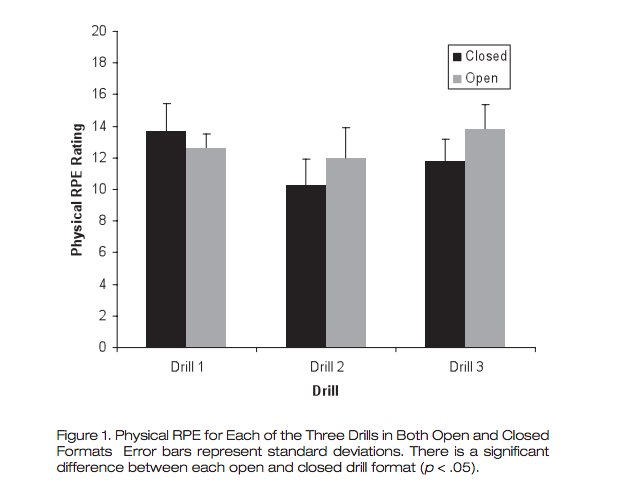

In 2008, Australian researcher Damian Farrow lead a study comparing open and closed agility drills in Australian Football athletes. His findings indicated a higher physical and cognitive Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) for the open agility drills. The author went as far as to say this:

“In conclusion, the open drills were generally more physically and cognitively demanding than the closed drills commonly used in Australian Football. Coaches and conditioning staff should prescribe open drills to elicit higher physical and cognitive training loads in a game-specific context”

Application :

Chasing is one our favorite ways to train game speed. When an athlete is chasing or being chased, there is a much greater neurological demand placed on the athlete than simply having them run on air at the sound of .a whistle. Even in our speed training, we try to keep the athlete’s environment as open and reactive as possible.

The curved run of a baseball athlete

Multi-Directional Sprinting

As many of you know, the highlight of the NFL combine is the 40-yard dash. Now while the 40-yard dash is a crucial aspect of getting noticed by scouts, the 40 is not truly indicative of football game speed. Every year there are guys who run terrible times at the combine, but then go on to have great careers. Those guys are are often called “gamers” by analysts.

How many times does a football player run 40 yards straight with nothing in front of him?…Rarely on the field during an actual game do athletes run in a straight line for any extended time, let alone 40 yards on a field. In reality, athletes run in many different angles and body positions during a game. For those types of runs, the athlete must not only consider their angles and body positions, but they must also consider the angles and positions of their opponents as well

Application:

Curved and Lateral Running

Let’s take a look at baseball as an example. Being fast around the bases isn’t just about running in a straight line, it’s about the angles an athlete takes to touch the base and if they can maintain or increase their speed as they run around it.

A lateral run is a movement where an athlete is running while his upper and lower body are not necessarily facing the same direction. For example, thing about a baseball outfielder running back towards a ball. His lower half is taking him towards the outfield wall, but his torso may be turned, looking back towards the infield. That movement occurs frequently in sports, yet is rarely emphasized in training.

After reading this article, you probably notice a common theme here…a coaches job is to prepare their athletes for the game. With speed being such a crucial element to most sports, we strongly believe that incorporating elements of game speed into training programs makes for a more prepared and well rounded athlete.